The Masonic Pageant

The 29 Masonic Degrees of the Scottish Rite

20th Degree

MASTER AD VITAM

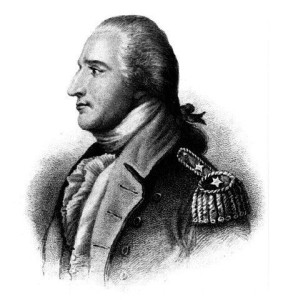

“To the most brilliant soldier of the Continental army… winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution and for himself the rank of Major General.”

Dedication on a monument to Benedict Arnold at Saratoga that does not mention his name.

The Stage Drama

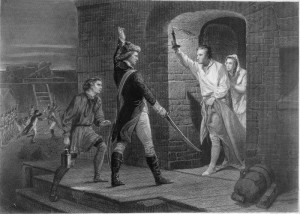

The time is November of 1784, one year after the Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolution and acknowledged American independence from England; the place is a Blue Lodge in Richmond, Virginia. George Washington is acting as Worshipful Master of the lodge. The cast of characters consists mostly of famous historical men (Washington, Lafayette, etc.) and portrays an imaginary scenario of their post-war relationships as they might have been influenced by their shared Masonic brotherhood. There is talk of a British officer who was a Mason and who infiltrated American Masonic lodges to spy and pick up military information. Then Benedict Arnold makes an appearance. From this point on the principal activity involves a dialogue between Washington and Arnold, who has returned to America from England and is seeking the forgiveness of his brother Masons for his treacherous behavior during the war. He does not succeed and Washington exiles him from America forever. Arnold is escorted back to his waiting ship and returns to England, a broken man.

This is the second of Northern Jurisdiction’s “Americana” degrees. It is a drama of the American spirit, confronting the challenge of disloyalty and treason. Masonic principles and leadership are subjected to a crucial test. The degree demonstrates the Masonic condemnation of all who conspire against the security of a nation and the happiness of the people.

Historical Background

On a beautiful spring morning in Philadelphia in 1780, the city’s former Military Commandant, Major General Benedict Arnold, sat at his desk, shaking his head in despair and thinking of suicide. His office was in his home, the beautiful Masters-Penn mansion at 6th and Market Streets. This building was so splendid it would later become the presidential mansion for George Washington and John Adams.

The reason for Arnold’s despair was easy to understand: his world, his career and his life were crumbling around him. He had married a beautiful socialite woman twenty years younger than himself and had been forced to live a lavish lifestyle that he could not afford. His meager salary from the Army had not been paid for two years, the new American currency was steadily plunging into devaluation from rampant inflation and the Continental Congress was in a shambles. He had wasted his wife’s dowry in disastrous investments and had tried to redeem his fortune by graft and profiteering, practices which, when discovered by a hostile city council, had resulted in a court martial. His only friend in the military, George Washington, had publically rebuked him with humiliating language. On his present course, he was headed for debtor’s prison and ruinous disgrace.

He could see only two ways out of his looming dilemma. One was suicide. The other was an equally terrible choice, one that made the patriotic Arnold sick in his soul but one that he had been contemplating for several months. In March of the previous year he had been forced to resign his post as Commandant. The court martial had isolated him from his few supporters in the Army and his almost total lack of social graces had turned away his even fewer friends in Philadelphia’s snobbish social circles. He now had no one to turn to except his wife, Peggy Shippen Arnold, a pro-British Tory who, years before, had been courted by Captain John Andre, a British officer in the then-occupied city. She had a connection with the enemy, one that Arnold could use.

How had his life come to this, he wondered. He loved his country. He was a brilliant strategist and fearless on the battlefield. He had sacrificed his health, his fortune and at times even his personal pride in his service to the Colonies. His friend, Washington, the most respected officer in the Continental Army, had spent half of his campaigns running away from the British. It was well known that as British generals pursued Washington across New Jersey, they had their buglers sound the fox-hunting call to show their contempt for him. On the other hand, when the Brits heard that Arnold was coming, they frequently found a plausible excuse to execute an about-face and march the other way. Arnold felt that, by all rights, he should be an honored warrior, basking in the admiration of his countrymen and enjoying the rewards heaped on him by a grateful Congress. What had gone wrong?

Most historians now agree that the most resourceful, brilliant and competent commander of American forces during the Revolutionary War was Benedict Arnold. Why did such a courageous, gifted man turn traitor? Let’s examine Arnold’s military career and see if we can find out what drove this battlefield genius to his own destruction.

Benedict Arnold was born on January 14, 1741 in Norwich, Connecticut. His alcoholic father left the family in reduced circumstances and Arnold was apprenticed to his two cousins as an apothecary (druggist). Like Washington, he fought as a red-coated British colonial auxiliary in the French and Indian War (1754 – 1763). In one of the engagements his battalion was forced to surrender a fort to the French, who had promised safe passage to the fort’s inhabitants. But as soon as the British laid down their arms, the Indian allies of the French massacred and scalped the women and children while the French soldiers looked on, doing nothing to stop the savagery. This instilled in Arnold a lifelong loathing and distrust of the French.

After the war, he soon had his own apothecary shop and then his own ship, which he sailed to the West Indies. He became deft at smuggling, an honorable and commonplace practice among sea-going American colonists. They, like most Americans, had nothing but contempt for England’s restrictive and crippling customs laws. During his travels he may have been, like many sea captains of the time, initiated into Blue Lodge Masonry on one of the British colonial islands in the West Indies. Alternatively, he may have been initiated into a military lodge while serving in the 15th Regiment of Foot under Lord Jeffrey Amherst during the French and Indian War. Hiram Lodge No. 1 of New Haven, Connecticut has him on the books as a member in 1765.

Back at home in New England, Arnold acquired a commission as the Captain of the Governor’s Second Company of Guards. When the Revolution broke out and news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord reached him, Arnold, without orders, marched off to the action with his men. He had acquired a taste for combat in his youthful campaigns during the French and Indian War. He paused long enough to request and receive a letter of authority from the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to capture Fort Ticonderoga. The fort was considered a prime target because it protected the southern tip of Lake Champlain against a feared British naval incursion from Canada. The British, with no need for the fort in peacetime, had allowed the defenses to fall into ruin. Rumor also had it that only 12 or 15 old British pensioners (retired soldiers) manned the fort. The capture of Fort Ticonderoga would be a plum assignment, indeed.

Other people thought so, too. When Arnold arrived at Ticonderoga with his Massachusetts permit, he found that the rival colony of Connecticut had hired Ethan Allen and his mercenary Green Mountain Boys to take the fort. These characters were not regular soldiers by any stretch of the imagination. They were an undisciplined armed gang, closer to Robin Hood’s Merry Men than to a troop of militia. They laughed at Arnold with his fancy officer’s uniform and his letter from the Committee of Safety. Arnold, who was supposed to have been the CO (Commanding Officer) of the operation, was forced to share command with the gigantic 6′ 6″ Allen, a gruff, hard-drinking frontier character.

On May 10, 1775, the fort was easily taken, mostly because the old soldiers inside hadn’t known that there was a war going on. Allen claimed in his memoirs that he had shouted “I take this fort in the name of the great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!” In fact, he kicked open the door to the fort’s commanding officer’s quarters and yelled “Come out of there, you damned old rat!” The Green Mountain Boys celebrated their victory by breaking into the British rum stores and getting stinking drunk. This did not improve their social graces and they mocked the prickly Arnold mercilessly.

If that weren’t bad enough, a Massachusetts officer with whom Arnold had previously quarreled reported back to the Committee of Safety, maliciously minimizing Arnold’s role in the fighting. Then, when Arnold returned to Massachusetts, the Committee of Safety refused to reimburse him for his out-of-pocket expenses. (Sometimes the CO of a financially-strapped colonial militia unit would pay for his men’s uniforms, ammunition and supplies, with the understanding that the government would settle accounts with him later). Arnold had to get a lawyer and take the case to the Continental Congress before the Committee of Safety paid the whole amount.

Ticonderoga was only the beginning of what was surely the most difficult, acrimonious and vituperative military career ever endured by a brilliant and courageous officer in the history of this nation. Each of the American colonies considered itself a small separate political unit unto itself. Rivalry among them for supremacy in the emerging nation was sharp. This had placed Arnold, the least diplomatic of men, in a vicious political confrontation between Connecticut and Massachusetts and – true to his nature – he had not behaved very well. He soon made for himself a small army of well-connected enemies in Congress that would plague him for the rest of the war.

Next came Washington’s ill-conceived scheme to invade Canada. He thought that if we arrived in Quebec with a show of force then surely the French-Canadians would rise up and join us in overthrowing their British overlords. They would then petition Congress to welcome them as the 14th colony. Remember President Kennedy and the Bay of Pigs, when the war pundits in his administration were sure the Cuban citizenry would join our invasion force and rise up against Castro? Kennedy refused to give the invading rebels air support, the Cuban people remained loyal to Castro and the whole affair became a fiasco of historic proportions. The invasion of Canada was Washington’s Bay of Pigs.

The French Quebecois still remembered the French and Indian War and wanted no part of us. They lived under an unusually mild British rule. The Colonial Office in Whitehall (Britain’s Foreign Office headquarters near London) had allowed them to keep their French language and their Roman Catholic religion and had left them alone to live impoverished but semi-autonomous agrarian lives in peace. They saw no need to ally themselves to a bellicose group of hard-drinking English-speaking Americans who would look down on their language, their ethnicity and their Church.

Washington promoted his friend Arnold to Colonel, and, for all practical purposes, put him in charge of the doomed invasion. But before he even got near the border, Arnold was betrayed by an Indian scout who handed over his invasion plans to the British. Having lost any element of surprise, the invasion failed miserably and his enemies in Congress wrongly blamed Arnold, who had fought bravely. During a major engagement on December 31, 1775, Arnold took a .75-caliber musket ball in his right leg. He refused let his orderlies carry him from the battlefield. He lay in the midst of flying musket balls, waving his sword like a marshal’s baton and barking orders from his litter.

Afterwards, while evacuating Montreal, Arnold “liberated” some desperately needed supplies – food, boots and blankets – from captured British stores. This was perfectly acceptable practice at that time and should have garnered no censure. But his enemies in the Congress brought him up on charges of plundering (enemy stores!) and demanded his arrest. His friend Washington and General Horatio Gates (a British officer who had retired from the Army and, when the Revolution broke out, joined the American side) managed to exonerate him. Both knew that a man of Arnold’s abilities would be far more valuable commanding an Army unit in the field than languishing in a jail cell.

In the fall of 1776 the British began their anticipated naval incursion from Canada down into Lake Champlain. They planned to retake Fort Ticonderoga and establish a beachhead on the southern tip of Champlain that they could use as a staging area for amphibious troop landings. This would constitute a dagger thrust deep into the heart of the colonies, splitting New York from New England. Washington once again called on Arnold, promoted him to Brigadier General, and sent him up to Lake Champlain to handle the matter.

The haughty British naval officers knew that they had the best navy in the world. They assumed that any colonial officer that Washington could dispatch to counter their offensive would be a hayseed and a landlubber with no knowledge of naval tactics. They were wrong. Arnold had been a sea captain and a world traveler; here he was able to put his maritime experience to good use.

When they got to the shores of Champlain the Americans found few usable boats to commandeer so Arnold ordered trees cut down and small boats built on the spot out of green, unseasoned timber. To set an example, he grabbed an ax and went to work. Soon he had assembled a fleet of over 15 small boats, each big enough to carry several cannon. These were small-bore field artillery pieces with large clumsy wheels, not the large-bore deck-mounted 25-pounders with small wheels that the British ships carried. And, of course, none of his rural farm-boy militiamen were trained in naval warfare.

It did not matter. On October 11, 1776, Arnold lured the British ships into a narrow passage between the shore and Valcour Island where they had no sea-room to maneuver. The wind died down and the huge British ships of the line became unmanageable. Arnold’s small boats were not dependent on the wind and his men rowed them right up to the British ships, safely under the naval cannons’ long-range arc of fire. The Americans gave the larger ships such a close-range pounding that the Brits were forced to retire and return to Canada. By the time they could regroup for another assault, winter had set in and Lake Champlain was frozen over. By the following spring the Americans had garrisoned the region with so many troops that the opportunity for an unopposed amphibious landing by the Royal Marines had passed. Another naval invasion was unfeasible.

The Battle of Lake Champlain, while not a complete victory, had been the greatest success any American commanding officer could boast of up until then. A bunch of farmers in rowboats had humiliated the mighty British navy, the best in the world! The British General Staff realized that the rebels now had a military genius in their ranks. Putting down this rebellion was not going to be a stroll in Hyde Park.

And what was Arnold’s reward? Congress censured him for the loss of ten boats! They also refused to grant him seniority of rank (that is, they would not recognize his time in grade) and promoted several younger officers over his head to flag rank. These newly promoted men would now be able to give him orders. In their arrogance, Congress had not even consulted Washington on the promotions and Washington was unhappy about it. As Commander-in-Chief, he was not accustomed to being snubbed by civilians. He wrote a letter to Congress praising Arnold and recommending that they restore his seniority. The letter was ignored, another snub. Washington was infuriated but held his temper, an art Arnold never learned.

Arnold, fuming, marched his men down to Philadelphia to confront his enemies personally. On the way he routed a superior force of British Marines who had made an amphibious landing on the beach and who were burning the town of Danbury, Connecticut. Arnold and his army chased the Brits back to their boats and continued on their way. Congress nervously eyed the approach of this short-tempered military prodigy, much as the Roman senate had eyed Julius Caesar’s march on Rome in 49 B.C. and the French had regarded Napoleon’s advance on Paris, after he escaped from Elba, in the spring of 1815. Like them, Arnold was accompanied by a victorious, battle-hardened army loyal to him. And, like them, Arnold was noted for his short temper and his abrupt, unexpected actions. Congress abruptly did an about-face. They commended Arnold on the victory at Danbury and promoted him to Major General. However, they still would not restore his seniority. Neither would they repay him any of his recent expenses. Arnold replied as only Arnold could: in July of 1777, he resigned his commission.

And then, on the same day, asked Congress to put his resignation on hold. Washington had, that afternoon, requested him to take command of a large force of men and proceed north at once. There was trouble brewing north of Albany, near a town called Saratoga. That meant some good fighting was in store and the always combat-ready Arnold, who enjoyed the battlefield more than the boardroom, could not pass up the opportunity.

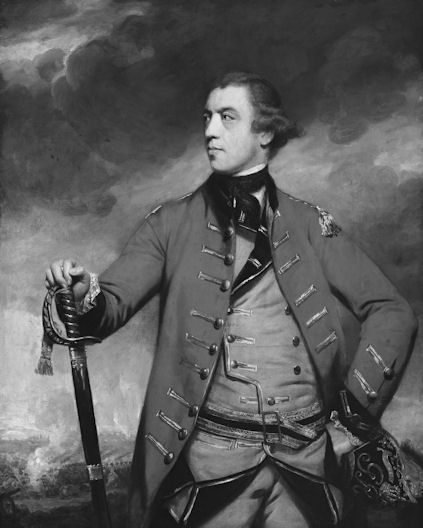

The British once again were attempting to capture the Hudson River Valley and split New York away from New England, paralyzing the American cause. This time, thanks to Arnold’s brilliant maneuvers at the Battle of Lake Champlain, they had no convenient staging area at Ticonderoga. They would have to start their assault from the far-away Canadian border. A British major general, John Burgoyne, a vain actor, dandy and playwright nicknamed “Gentleman Johnny”, planned to push down through the wilderness route along Lake Champlain to Albany where he would join forces with British General William Howe, who Burgoyne assumed would be coming up from New York City, Howe’s last reported position.

Thinking the campaign would be an easy path to military glory, the well-connected Burgoyne had gone behind the back of his superior officer in Canada, Sir Guy Carleton. Burgoyne had sailed to London a few months earlier to lobby Parliament for Carleton’s position of Commander-in- Chief of Canada. He was heavily dependent on the support of his patron, Lord George Germain. Germain had started his political career as George Sackville and had worked his way up in the army to become Colonel of the 20th Foot (or Lancashire Fusiliers). During the Battle of Minden (August 1, 1759) in the Seven Years war, the French threatened to overrun Sackville’s position and he deserted his regiment and fled from the battlefield. The War Office charged him with cowardice in the face of the enemy and cashiered him from the service. By exploiting his friendship with George III, he managed to return to London, move up in government and eventually acquire the title of Lord Germain.

With Germain’s influence, Burgoyne succeeded. He sold Parliament on his own plan to split New England away from the other colonies. He would march down from Canada through the wilderness toward Albany, retaking Ticonderoga along the way. In England, his friend Lord Germain, head of the War Office, would issue written orders to Howe, thought to be operating around Manhattan Island, ordering him to march north up the Hudson Valley to join with Burgoyne’s troops at Albany. The thought that Howe would ignore such orders never occurred to anyone. Once at Albany, Howe would relinquish his command and put himself under Burgoyne’s authority. So Carleton was by-passed in favor of the better-connected Burgoyne.

John Burgoyne had entered military service at the age of 15 and had used his prominent family’s influence to climb up in rank to major general. Although a competent officer who had seen a great deal of action, he was completely unfamiliar with the American wilderness and was relying heavily on Howe’s military experience in North America which he intended to exploit when they joined forces.

But Howe, tiring of besieging New York City, had other plans. On his own, with no orders from the war Office, he decided to travel south and take the rebel capital, Philadelphia, in July. Unbeknown to Burgoyne, Howe boarded his men onto naval troop transports and sailed down the New Jersey coast. Some reports indicate that, for some reason, he spent the entire month of August at sea, finally sailing up the Chesapeake Bay and attacking Philadelphia in September. He took the largely pro-British capital with little fighting and settled down for the fall.

Howe was a tough, courageous soldier who had distinguished himself during the French and Indian War. During the British assault on Quebec on the 13th of September, 1759, a French sniper killed his commanding officer, Gen. James Wolfe. Howe took command, led the British assault on the Heights of Abraham and captured Quebec City. When the Revolution broke out, the Crown had appointed him Acting Commander-in-Chief of all British forces in the Colonies.

But age and battlefield hardship had mellowed Howe’s tastes and blunted both his energy and his decision-making abilities. He had become fond of good food and gala social events. Once in Philadelphia, he fell in love with the clean, charming capital city. Philadelphia was full of upper-class American Tories and British sympathizers who had no qualms about fraternizing with British officers; parties and balls abounded. Benjamin Franklin, in France at the time, joked that it was not so much that Howe had captured Philadelphia but rather that Philadelphia had captured Howe.

Howe knew very well what Burgoyne was up to, and he had no intention of surrendering his command to the pretentious fop. The pleasure loving general was in no hurry to begin a long march north through the New York wilderness in the late fall with a harsh winter coming on, just to support the ambitions of a man he despised. He was also in no hurry to face companies of dead-shot American riflemen who, it was rumored, could hit a man’s head at 300 yards. For personal reasons he found the company of his mistress, the wife of one of his junior officers, to be more agreeable and he stayed put in the City of Brotherly Love.

Meanwhile Burgoyne was struggling through the wilderness with a company of 3,700 British regulars, 3,000 Hessians, 250 Canadians and American loyalists and 400 Indians. They were accompanied by a cumbersome train of baggage wagons, cooks and personal servants. There were also a large number of women, the wives and “companions” of his officers. Most of his artillery was being floated on barges down nearby Lake Champlain.

Burgoyne’s forces also had to waste time and energy diverting their march to retake the now increasingly irrelevant fort at Ticonderoga with the intent of turning it into a staging area. The mere approach of Burgoyne’s army so unnerved the fort’s defenders that they promptly deserted their post and disappeared into the forest. After many hardships on the wilderness journey, Burgoyne finally met the Americans near Saratoga on September 19, 1777. He seemed to regard the American colonials as an inferior breed of “natives,” one step above the Indians, who in turn were considered to be one step above the forest animals. He fully expected them to run away in a panic when they caught sight of his troops’ stunning red uniforms and heard the unnerving skirl of the regimental bagpipes. He had a few lessons coming.

His first lesson was the loss of an “impregnable” fort manned by two thousand British and Hessian troops. Arnold, serving under the command of General Horatio Gates, was the only volunteer who offered to take the fort. He had to do this with less than a thousand men, all that the jealous Gates would allow. He succeeded by convincing the fort’s defenders that he was leading a force of several thousand soldiers and Indians. He knew that the British and Germans were terrified of the savage Indians, who routinely tortured captives to death. Sure enough, when they heard the American soldiers’ imitations of Indian war whoops, the fort’s defenders panicked and advanced smartly to the rear, disappearing into the pine woods. Arnold entered an empty fort.

The Battle of Saratoga was actually two separate battles, fought 18 days apart. The first was the Battle of Freeman’s Farm on September 19, 1777, in which Arnold, alone, personally led the Americans to victory. This was too big a feat to ignore and Gates was now becoming wary of Arnold’s bravery and leadership skills, two attributes that the cautious Gates lacked. Afraid that Arnold would outshine him, Gates falsified his written reports and refused to acknowledge Arnold as the officer responsible for the victory. He also began to surreptitiously reassign Arnold’s troops to other officers. When Arnold found out, he exploded and quarreled with Gates in front of Gates’ staff. Gates, who had been looking for just such an opportunity, relieved Arnold of his command and confined him to quarters.

Arnold, furious, paced and fumed in his tent until the second major engagement, the Battle of Bemis Heights, broke out on October 7. Unable to remain still while other men were fighting and dying for the American cause, Arnold sent for his horse. He galloped off to the front lines, waving his sword. Gates had concentrated his forces on the British right and left flanks, hoping that the British line would coalesce on either flank and become vulnerable in the center. Under Gates’ cautious plan of attack, the center held and the Americans were being mowed down by timed, disciplined volleys of musket fire from Burgoyne’s regulars.

Then Arnold appeared out of nowhere. He quickly sized up the situation and saw that the American advance under the cautious Gates was too slow, allowing the Brits too much time to reload their muskets. A trained British soldier could reload and fire his smooth-bore Brown Bess musket every 16 seconds. Arnold correctly surmised that if the Americans charged at a run they could reach the British line between volleys and settle the matter with bayonets.

Also, the British-born Gates wasn’t making proper use of the long-range Pennsylvania rifles carried by General Daniel Morgan’s Rifle Company, relying on his regular soldiers’ conventional-issue muskets instead. The smooth-bore Tower of London musket had an effective killing range of only about 70 yards. An individual soldier could not aim his musket with any accuracy. Only by lining up a regiment of several hundred trained men who could raise and fire their muskets simultaneously on command could a commander hope to do any damage to an enemy.

This was the original purpose of close-order drill (Right face! Left face!, etc.). Today officers use the drill only for ceremonial purposes or as an exercise to teach recruits obedience to commands. In Arnold’s day it was a very practical and necessary maneuver that was used on the battlefield to wheel a marching column of men into an effective firing line in a matter of seconds. In the same vein, the modern-day manual of arms (Present arms! Shoulder arms!, etc.) were the commands used to ensure the uniform delivery of musket fire and subsequent reloading of weapons on command.

In the hands of a practiced shooter a Pennsylvania rifle with a grooved bore could kill at 300 yards. Arnold, ignoring the fact that he had no command but knowing that American rifle fire was especially demoralizing to British troops, ordered Morgan to direct his riflemen to lay down a long-range volley. Morgan, who had served with Arnold before and who respected him, complied and Morgan’s Rifles opened fire, safely out of range of the British muskets. Their volleys were devastating and the British, realizing they were now under rifle fire, began to break ranks and run.

Riding out in front, Arnold led the Americans in a charge that broke the British line. As the Brits were retreating, Arnold’s horse was shot out from under him and fell on his wounded leg, further injuring it. Burgoyne was forced to retreat and wait for Howe to arrive with reinforcements.

He’s still waiting. Howe, comfortably ensconced in Philadelphia, could not have cared less whether Burgoyne was winning or losing his battles in the wilderness and saw no reason to leave the charming city for an unwelcome campaign in the cold, wet forests of northern New York. He only intended to move if he received direct orders from London to do so. The orders would have to come from Burgoyne’s patron, Lord George Germain, the Secretary of War.

The story goes that Lord Germain was eager to go off on a weekend holiday in Kent. On the way, he had his carriage stop at the War Office so he could sign the requisite orders. There were two sets of orders, one for Burgoyne to conduct his march south from Canada and one for Howe to move north and meet him at Albany. Germain signed Burgoyne’s orders but the orders for Howe had been sloppily written and he refused to sign them until a better copy was made. This would take about three quarters of an hour, and he didn’t want to keep his carriage waiting. Germain’s office staff, a careless, slovenly bunch of civil servants, assured him that they would get the rewritten copy of Howe’s orders to his holiday retreat by the next day, in plenty of time for him to sign them and put them on the next ship to America. As soon as Germain left, they quickly mailed Burgoyne’s orders so that they reached a departing ship just in time. Then, without waiting for the fresh copy of Howe’s orders, they all went home for the weekend. The orders for Howe, when they arrived, were placed on Germain’s desk, where they languished unnoticed for a couple of days. Germain’s Deputy Secretary, a man named D’Oyley, found the papers and, knowing Germain wouldn’t be back for several days, signed them himself and got them onto the next ship departing for the colonies.

There are at least three versions of what happened next. One version is that the ship with Howe’s orders met with contrary winds and was delayed so long that by the time the orders reached Philadelphia, Howe was no longer there, having been forced to evacuate the city. Another version is that Howe received the orders in time but, seeing D’Oyley’s signature, thought (wrongly) that they were not binding and waited for orders signed by Germain to arrive. A sailing ship, even with favorable winds, could take three weeks or more to cross the Atlantic and Howe was quite willing to spend those weeks in Philadelphia. Yet another version holds that Howe received the orders, knew that Deputy D’Oyley’s signature made them binding, but ignored them anyway.

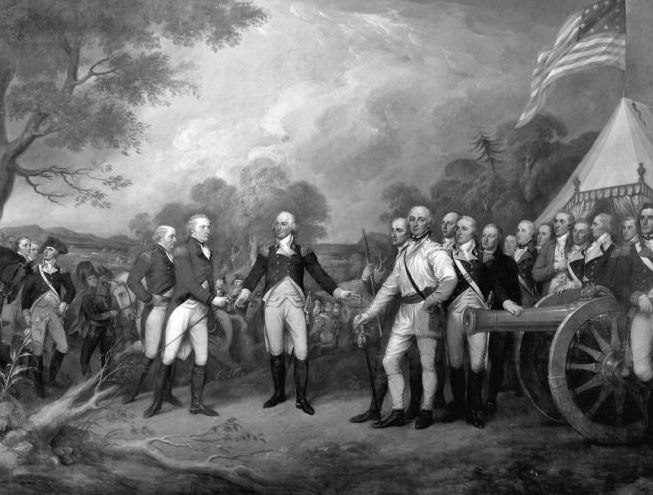

The last version is most probably the correct one. Howe detested Burgoyne, knew that his campaign was doomed to failure and had already written the War Office, saying that he had no intention of helping Germain’s toady. Whitehall, the British War Office, had given Britain’s general officers, conducting a war in a far-away alien land, a great deal of latitude in making their own decisions, so Howe’s independence was not as surreal as it may seem in today’s world of rapid communication. Every officer in the British armed services despised Germain as a sycophant and a coward, and his orders were frequently ignored. Meanwhile, up in northern New York, Burgoyne had no recourse but to surrender to the American forces, which he did on October 17, 1777.

I cannot overemphasize the importance of our winning at Saratoga. Saratoga was the major turning point of the war, as important a battle in its own time as Midway would be to America in 1942. In 1777 the reason was France. Until our victory at Saratoga, we were barely holding our own against Britain. France feared to come to our aid as long as it looked like we might lose. The Battle of Saratoga exposed Britain’s many Achilles’ heels – communication time, distance, logistics, incompetent officers and an inflexible bureaucracy. Also displayed was the brilliance, courage and fighting ability of the American troops.

After our victory at Saratoga France officially declared her alliance and flooded us with men, muskets and ammunition. French warships came over to make up most of our naval force and well-trained professional French soldiers quickly arrived to double our number of ground troops. We soon had large artillery parks of excellent French cannon. Without French aid our cause of independence, popular with only about one-third of America’s colonial population, probably would have sputtered out.

Most Americans remembered all too well the butchery that England had subjected the Scottish Highlanders to after the failed Jacobite rebellion of 1745. We would have had to sue for peace under the most humiliating terms to avoid a similar orgy of vindictive hangings and public torture. But with France on our side, we backed the British into the sea and forced them to ground their arms at Yorktown.

Saratoga was key to our success in the War of Independence and the victory at Saratoga was unquestionably Arnold’s. But Gates made sure that he, not Arnold, received the credit. Arnold’s contribution was once again ignored. Congress finally granted him his seniority in rank but it came too late to do his military career any good and much too late to mollify Arnold’s savaged feelings. A proud fighting man, he was now a cripple with little money and few friends.

After his wound at Saratoga, Arnold was sent to a military hospital in Albany to recover. After several months of agony and primitive medical care, he left the hospital with the wounded leg two inches shorter than the other. He could no longer mount a horse unaided and walked only with the greatest difficulty using a cane. Since Howe had evacuated Philadelphia, Washington, perhaps as a consolation prize, appointed Arnold to be Military Commandant of the city.

Irony plays tricks on us all, and some of the tricks can be horrendous. Arnold had survived everything the battlefield could throw at him and had laughed in the face of death and crippling injury. But the peaceful occupation of a beautiful city dealt him a deadlier wound than any British musket ball could have.

It all came down to a clash of cultures. In contrast to his days in the rough-and-ready colonial army, he now found himself in command of an environment that placed great value on wealth, manners and social status. Arnold, who had none of these, had no idea where to turn. He was a widower and began to court an attractive and boisterous young woman named Peggy Shippen.

Peggy was the youngest daughter of a prominent Philadelphia judge. At 18, she was not particularly thrilled by the attentions of a 38-year old, hook-nosed, pot-bellied, rough-at-the-edges officer who limped around on a game leg. If truth be known, she really missed the company of handsome young Captain John Andre, a British officer who had been seeing her during Howe’s occupation of the city. She came from an upper-class Tory family that was sympathetic to the British. Like many wealthy young Philadelphia girls, she had enjoyed the British occupation with its parties and balls and dashing, cultivated young officers from Britain’s upper classes.

Her father is said to have been chagrined at Arnold’s approaches. But I believe that, seeing that the American side was finally gaining the upper hand, it was he who persuaded his daughter to accept Arnold’s proposal. He would have looked on this as insurance against any post-war repercussions ensuing from the family’s blatant fraternization with the enemy. Peggy reluctantly agreed and became Mrs. Arnold. At the marriage ceremony Arnold – too vain to use a cane at his own wedding – had to be assisted down the aisle supported by one of his officers. The marriage elevated Arnold to a high social status that he could not afford; he and Peggy lived far above their means. She and Arnold threw lavish balls for Army officers and civilians.

The cash-strapped Continental Congress had been dragging its feet on payments to the Army and Arnold soon found himself over a year behind in his salary. To make ends meet, he ordered his soldiers to close down certain shops. He then forced the owners to sell him their merchandise at a steep discount and later resold the same goods at a profit. For a fee, he gave illegal passes to Tory merchants to leave the city, knowing that they intended to sell food and other goods to the British. He entered into a scheme with a group of speculators to purloin half the profits from the capture of a British ship that belonged to someone else. He boasted that he intended to resign from the army and use his naval skills to command a fleet of privateer ships and accrue a fortune. Privateers were privately owned and armed pirate ships that operated under a license from Congress. They could legally overhaul and board any commercial ship sailing under an enemy flag and steal its cargo.

On a board in the main hall of Philadelphia’s Customs House, the captain of every ship that was going to put out from the city’s busy port fastened a sheet of paper with the ship’s name, cargo and destination written at the top. Whoever wanted to invest in the ship would put up an amount of money as an early kind of maritime insurance. The investor would write his name and the amount of his investment on the paper under the name of the ship (the origin of the term underwriter). If the ship reached port successfully, its cargo would be sold and every investor who had underwritten the ship would receive a share of the profits from the sale proportionate to his investment.

Arnold and some of his friends invested in a large merchant ship, the Charming Nancy. They did not underwrite the ship publicly and kept their investment private. Although legal at that time, this was definitely a questionable act for the Military Commandant of the city, who controlled access to Philadelphia’s busy port, to engage in without public knowledge. The ship carried a great load of merchandise and Arnold’s split from the sale would be significant. Shortly after the Charming Nancy left port, however, she was boarded by the crew of a New Jersey privateer. The privateer’s captain had spotted British warships off the Jersey coast and, fearful that her cargo would fall into British hands, forced the Nancy to turn back and dock in Egg Harbor, New Jersey, until the danger passed.

When the news reached Arnold, he panicked. He could not afford to lose his investment and, knowing the fragile nature of law enforcement among the half-patriotic, half-Tory citizenry living under the rigors of wartime conditions, was fearful that a mob would storm the ship and steal its cargo. Without any authority, he forcibly seized a dozen army wagons belonging to the commonwealth of Pennsylvania and dispatched them under armed guard to Egg Harbor. His soldiers retrieved the Charming Nancy‘s cargo and brought it back to Philadelphia, where Arnold and his partners sold it. Arnold then doctored his account books to conceal the transaction and the requisitioning of the wagons. This was the final straw for the city’s authorities and they pounced on Arnold.

The president of Philadelphia’s Executive Council, Joseph Reed, hated both Arnold and Washington with a passion. He had been biding his time and keeping note of Arnold’s activities. The Council quickly brought Arnold up on charges of improper conduct and demanded that the Army court-martial him. Washington, who would have preferred to handle the matter privately, had no choice.

The court martial took place at Norris’s Tavern in Morristown, New Jersey. Because of the hard winter and difficult travel conditions, it dragged on from December 23, 1779 until the end of January, 1780. Arnold, confident of an acquittal, acted as his own defense, limping up and down on a cane in full-dress uniform in front of the court-martial board members. He thought that, when the trial was over, he would be acclaimed as a national hero and he planned to make some money later on by publishing the transcript of the trial and the expected acquittal as a book.

But there was no acquittal. The court marshal found Arnold guilty on two counts: Requisitioning government wagons for his personal use and allowing unauthorized ships to dock in Philadelphia’s port. Even Washington, who had supported Arnold until that point, had to publicly rebuke him. In the rebuke, he called Arnold’s conduct “imprudent, improper and peculiarly reprehensible.” That rebuke, although it was nothing more than a formal slap on the wrist, was the final straw. Arnold never forgave Washington for what he considered a betrayal of their friendship.

Arnold was at his wits end and could take no more. After the court-martial conviction he had no hope of a post-war military career and he was now hopelessly in debt. At that time the courts could send a man to prison for an unpaid debt of five pounds, and Arnold owed considerably more than five pounds. Arnold knew that the law could not touch him in time of war as long as he was a flag officer in the Continental Army. His creditors would have to use the municipal police force to arrest him and Arnold was still a Major General who commanded a thousand bayonets. But he also knew that the war was coming to an end and that he would not be a General forever.

Arnold saw no way out; sometime toward the end of 1779 or the beginning of 1780 he decided to sell out to the enemy and opened negotiations with the British. His Tory wife fully supported his treason and, at her suggestion, he used her former boyfriend, John Andre, as a go-between. Andre was now a Major and the chief intelligence officer for Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander in Canada.

The British warship HMS Vulture, an armed sloop, ferried Andre to and from Canada along the largely unguarded Hudson River. Dressed in civilian clothes, he had no trouble contacting Arnold. The colonies were full of people with British accents and Andre blended right in. The British particularly wanted West Point, a fort that controlled access to the critical New York City area to ships coming south from Canada. Located on an S-curve of the Hudson, any ships that passed West Point would have to slow down and progress awkwardly within easy range of the fort’s huge cannons. The fort was perched on a high bluff and could rain cannonballs down on shipping in the river while the ships below would be unable to return fire upwards. Also, a heavy chain stretching between West Point and Constitution Island lay on the river bottom. Soldiers could quickly raise it at a moment’s notice and it would become an impassable barrier to any vessel sailing down river. West Point, in American hands, effectively confined the British navy to the northern half of the river. Arnold agreed to turn over West Point in exchange for 10,000 pounds, land in Canada and a commission in the British army.

Andre’s activities, however, did not go unnoticed. Washington had established his own personal secret service organization under the supervision of his confidant, Major Benjamin Tallmadge of Setauket, NY. Washington was getting word about reported seditious activities in New York City and requested Tallmadge, a former schoolteacher and a classmate of Nathan Hale, to establish a spy ring there. Tallmadge placed his boyhood friend, Abraham Woodhull, in charge of the New York operation and had him enlist their old friends and neighbors in near-by Setauket as civilian operatives in the spy network. The New York operation was code-named the Culper Ring from the code names of the New York contact – “Culper Jr.” – and his go-between with the Continental Army in Connecticut, “Culper Sr.”

Woodhull’s spies soon got word to Tallmadge and Washington that something big – very big – was afoot. It involved the sell-out of a major American military stronghold to the British. Washington knew that only a high-ranking officer could bring about such a momentous transaction and pressed his spies to find out the traitor’s identity and plans. Little did he suspect whom the culprit would turn out to be.

Meanwhile, Washington was starting to feel that he had been too harsh with his old friend and offered Arnold command of the left wing of the colonial army, a great coup for any officer and one that would have delighted Arnold a few years earlier. But Arnold used his crippled leg as an excuse and asked for command of West Point instead. Washington was happy to comply, thinking that now at least that particular stronghold would be in trustworthy hands. At last, events looked as though they were starting to come together for Arnold.

No sooner had Arnold taken command of West Point, however, when everything fell apart. When Andre tried to return to Canada after one of his visits, he could not find the Vulture. A squad of American troops patrolling the Hudson had forced it into hiding. Dressed in civilian clothes, Andre was trying to make it to the border on foot when three highway robbers who doubled as frontier militiamen waylaid him. Andre, a dandy who intended to marry well, was dressed foppishly in expensive clothes and his upper-class British accent marked him as fair game for the robbers. Who would punish them for despoiling a damned Tory? He had no money on him, but his beautiful shiny boots attracted the militiamen’s attention and they ordered Andre to take them off. To their surprise, they found papers that looked like military documents stuffed into the boots. The men could not read very well but they figured Andre must be doing something underhanded so they tied him up and took him to the local sheriff, hoping for a reward.

The sheriff, a civilian, could not make sense of the maps and documents but he saw that some of them bore General Benedict Arnold’s signature. And Arnold had scrawled his name on a margin of one of the pages. Relieved, the sheriff dispatched a rider to carry some of the papers to Arnold at West Point; this was Army business and the general would know what to do. After the rider had left, the sheriff sent another messenger to carry the rest of the documents to Washington’s headquarters in Connecticut. He spent the rest of the afternoon daydreaming of the reward he would get from Washington and Arnold for returning the stolen documents and turning over the thief, who now languished in the town jail. He imagined Arnold would be especially happy and would probably have him and his wife over for dinner at the Point.

Arnold, however, was not especially happy when he saw the papers that the rider delivered. He immediately loaded two pistols and bolted from his office. We could not take his wife and child with him so, before leaving, he convinced Peggy that she could persuade the authorities of her innocence in the matter by feigning hysteria. Down at the river’s edge he ordered two of his men to seize a boat and row him north up the river. When the men questioned his reasons for wanting to venture into enemy territory, Arnold leveled his pistols at their heads and informed them that they could either obey or have their heads blown off on the spot. Good soldiers, they decided to obey.

The papers intended for Washington were intercepted by the master spy-catcher Tallmadge who immediately saw what was going on. He gathered a squad of men and made a beeline for West Point to arrest Arnold but they arrived too late. The traitor was gone. Washington himself had arrived at the Point that very morning on a routine inspection visit. He was miffed that his old friend Arnold was not on hand to greet him. Then Tallmadge’s group galloped up and gave Washington the bad news. Washington, who knew nothing of Peggy’s compliance in Arnold’s treachery, was completely taken in by her phony hysterics and allowed her to return to Philadelphia with her child.

Arnold, thanks to his enthusiastic rowers, was able to find the Vulture which then took him safely up to Canada. Washington, stunned and grieving at his trusted friend’s treachery, offered to exchange Andre for Arnold but the British refused. Washington, in an uncharacteristic rage over Arnold’s treachery, had young John Andre hanged as a spy and Arnold, now a British officer, donned a red uniform.

For a while, Arnold fought as well for the British as he had for his own country. In Virginia, he asked a captured American officer what the Americans would do to him if he were taken. Supposedly the officer replied: “We would cut off your right [wounded] leg and bury it with full military honors and then hang the rest of you.” After the war, Arnold moved to London and was welcomed by King George but found a cold reception from the Tory government of Edmund Burke. Burke refused to put Arnold in charge of British soldiers on the grounds that, as a traitor, he was a dishonorable man. Arnold died in London in 1801, in considerable debt. His wife Peggy managed to repay all of the debt to the sum of 6000 pounds before her death in 1804.

Today, Arnold, his wife Peggy and their daughter, Sophia Phipps, are buried in the crypt of a Georgian-era church, St. Mary’s of Battersea, on the banks of the Thames. Their tombstone, donated in 2004 by an American well-wisher, is almost obscured by a large tropical fish tank; the brightly-painted crypt now doubles as the church’s day-care center.

Scholars have considered Arnold’s treachery to be particularly reprehensible because he committed it not from long-held principles but for entirely selfish and egotistical reasons. While he was undeniably a victim of circumstance and of his own abrasive personality, I believe that, during the years that he was a loyal American officer, he deserved better treatment from Congress and from Washington’s General Staff. Of course, our fledgling country – insecure and vulnerable – surely deserved better from this courageous, talented senior officer, one of the best in the service. In spite of the many unfortunate circumstances that bedeviled this brilliant, driven man, I don’t think that history will every exonerate Arnold, nor will his Masonic Fraternity.

Nevertheless, like it or not, we all owe Arnold a great debt. We owe him the victory at Saratoga. That victory gained us the French intervention that turned the tide against the mightiest empire in the Western world. We almost certainly owe him our independence.

The 20th Degree of the Southern Jurisdiction:

SECRET MASTER

This degree is quite different in the Southern Jurisdiction. It is all about teaching leadership by means of mystical geometry, particularly the numbers nine (3 X 3) and 27 (3 X 9). First, the candidate is taught nine virtues that Pike thought were necessary for the proper governance of a blue lodge. These are illustrated by nine candles representing the “nine great lights in Masonry.” The candidate is then lectured on no less than 27 more virtues represented by the image of a complex geometric figure containing squares, triangles and an octagon. Finally, he is given advice on virtuous government by nine famous lawgivers of history, including Hammurabi, Socrates and Confucius. The lessons of the degree are that truth, justice and tolerance are indispensable qualities for a Master of the Lodge and that example is the best teaching method known.

Recent Comments

- Frank on Introduction

- Nanci J Davids on Introduction

- Obdulia O Erno on Introduction

- Keith B Lucore on 29th Degree

- Del Z Didion on Introduction

Meta

- Register

- Log in

- Entries RSS

- Comments RSS

- WordPress.org